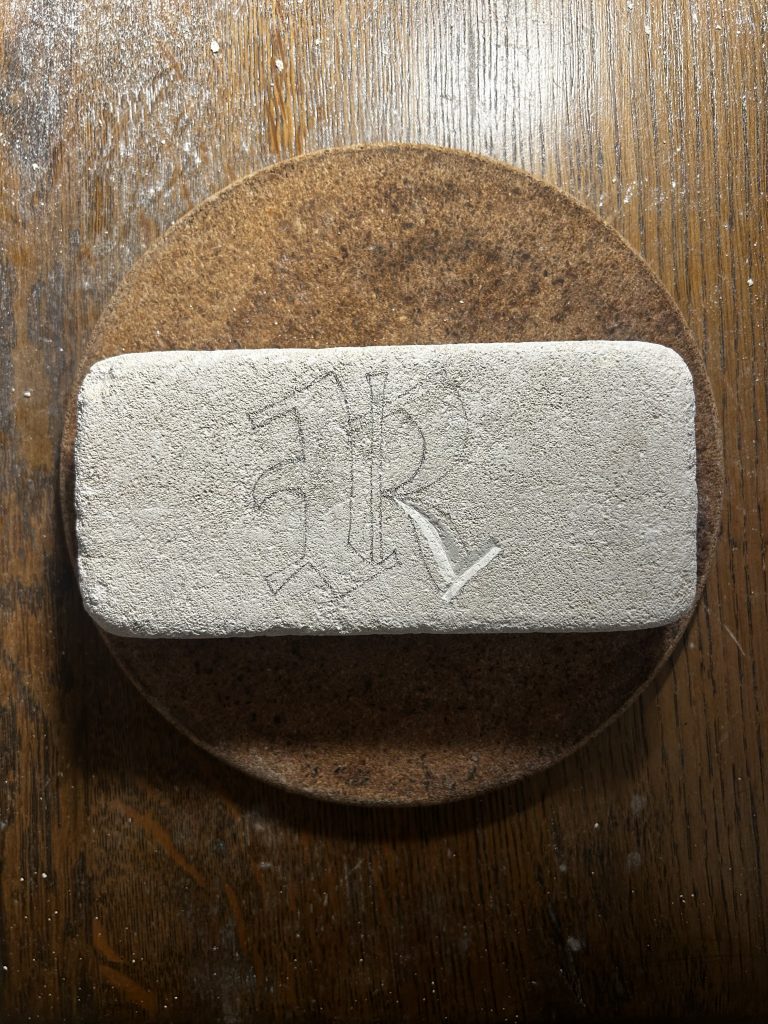

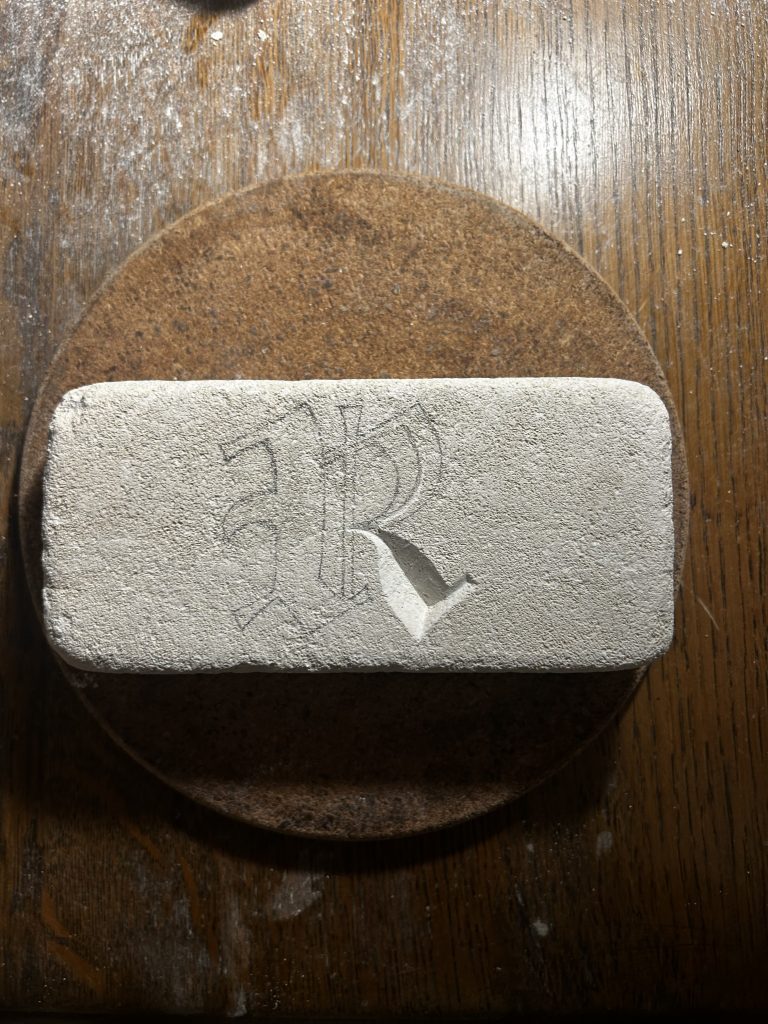

Draft 1

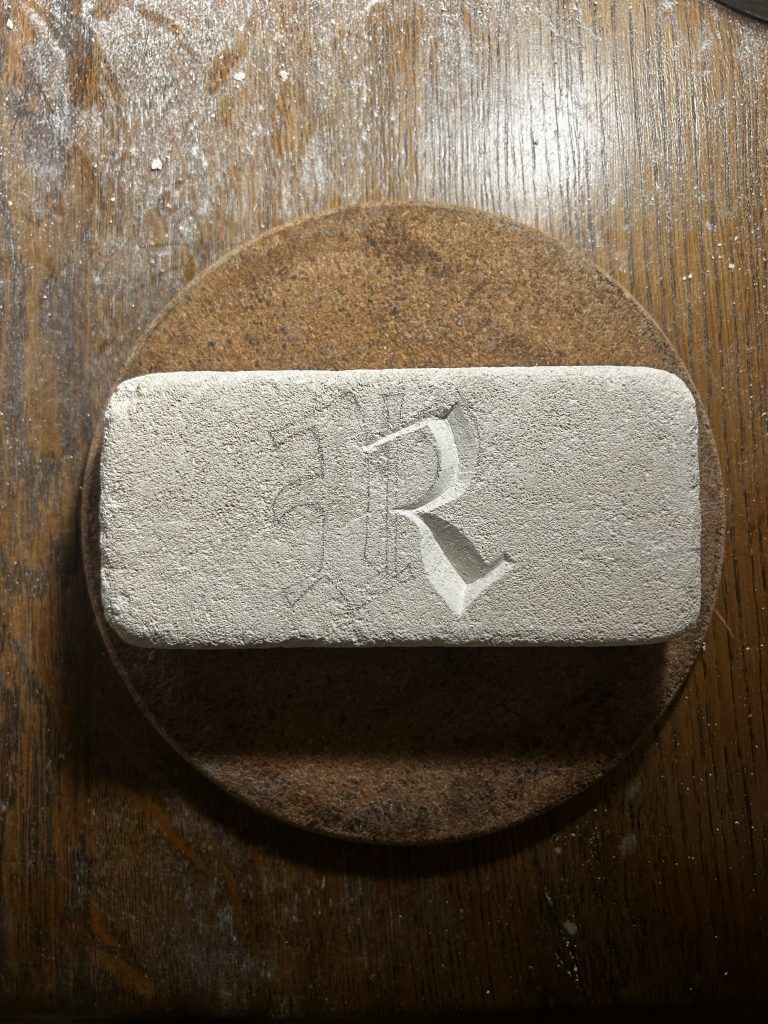

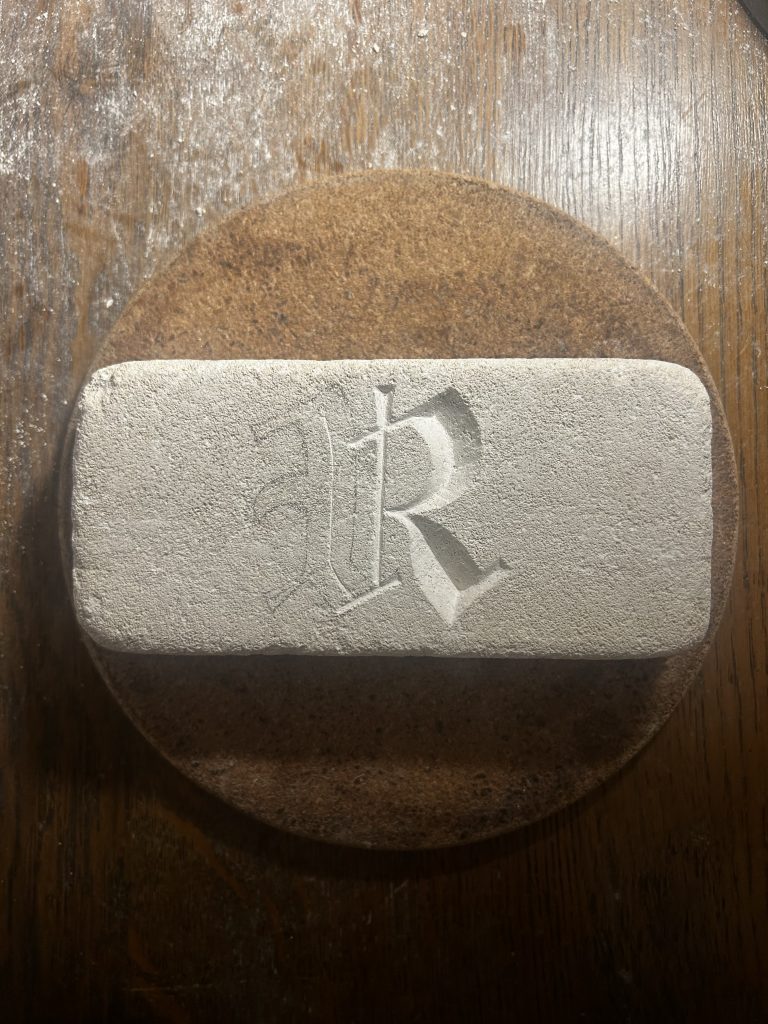

Draft 2

Rationale for the Inquiry

Lacking prior experience in typeface design, I opted to eschew digital software in favor of investigating the discipline’s absolute historical foundations.

In my first tutorial, Zarna asked me why I chose stone carving over digital software, aside from just the historical aspect. I told her that working on a computer feels like designing a typeface, but stone carving is different, it allows me to physically experience the process of a typeface being created from the very beginning.

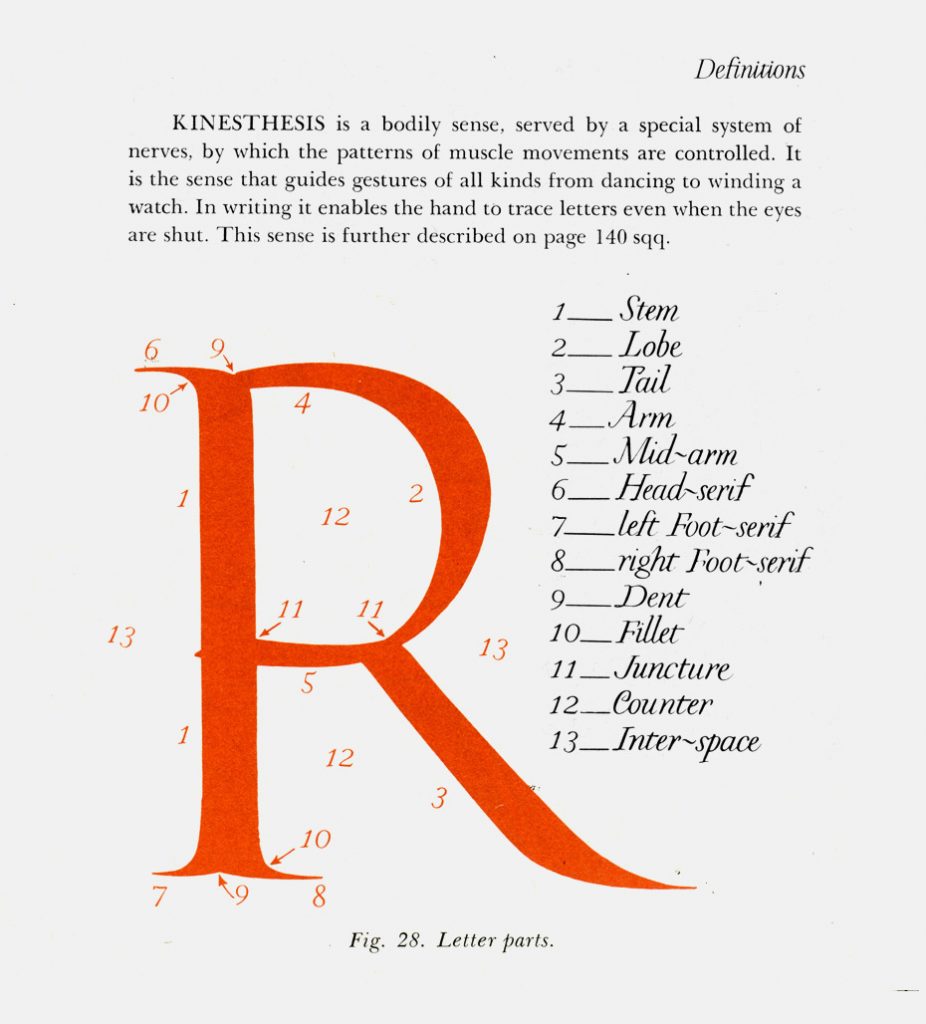

Through research into stone carving pedagogy, I identified a prevalent trend: the letter ‘R’ is frequently selected as the inaugural exercise for novices. This practice is notably visible in documentation from the Royal Academy of Art, The Hague (KABK), where workshop walls display a proliferation of student-carved ‘R’s.

This pedagogical preference is theoretically grounded in Father Edward Catich’s The Origin of the Serif. Catich posits that the ‘R’ serves as the definitive technical assessment, acting as a morphological microcosm of the Latin alphabet. It synthesizes three distinct structural components: the vertical stem (akin to ‘I’), the curved bowl (as seen in ‘P’ or ‘B’), and the complex diagonal leg. Consequently, mastery of the ‘R’ implies a transferable proficiency applicable to the remainder of the alphabet.

The copy piece

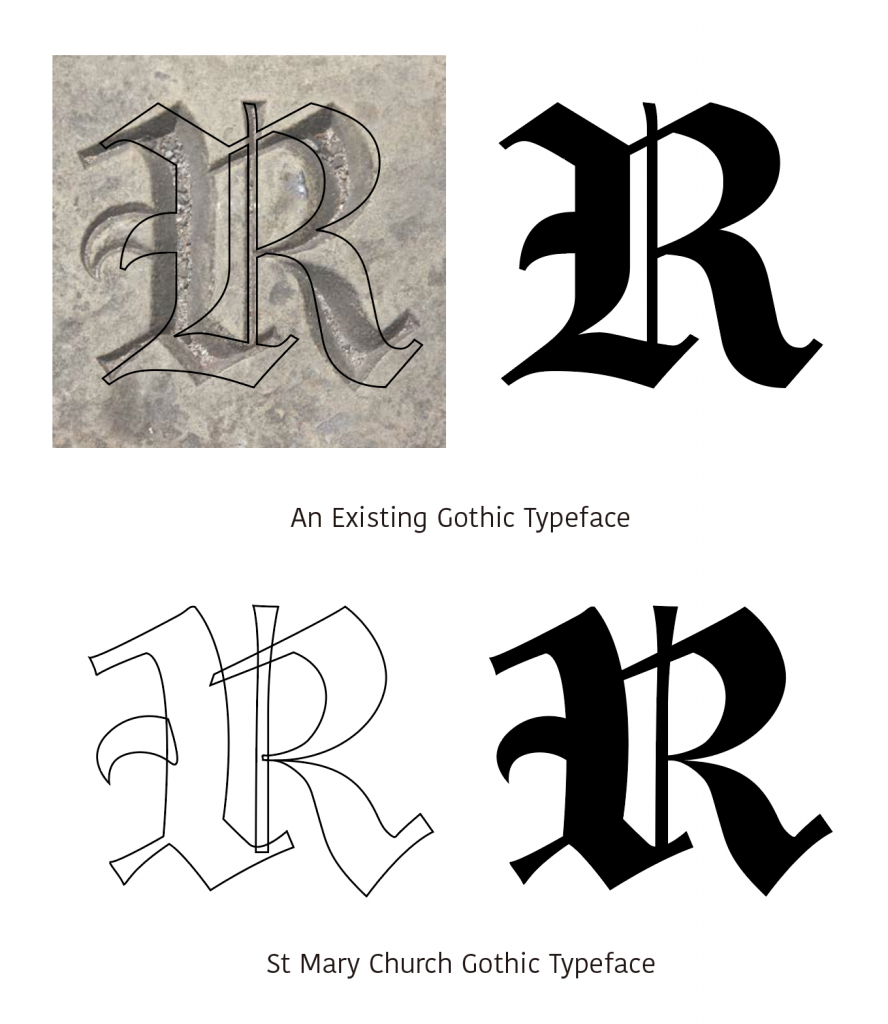

Informed by this rationale, I resolved to center my initial enquiry on the letter ‘R’. However, distinguishing my approach from the traditional Roman style, I selected a specific Gothic ‘R’ located at St Mary the Virgin Church in Manchester. This selection was strategic; unlike Roman monumental capitals, Gothic script is fundamentally calligraphic in origin. It was conceived for the fluid dynamics of the quill pen rather than the rigid subtraction of the chisel.

Translating this form into stone necessitates the transposition of fluid, pen-based gestures into unyielding matter. This approach tries to critically examine the material tension inherent in preserving calligraphic nuance through the subtractive process of carving.

St Mary the Virgin

Photo taken by Leo Reynolds

Carved by Andrew James

Bath stone

Exercise of the Trajan R

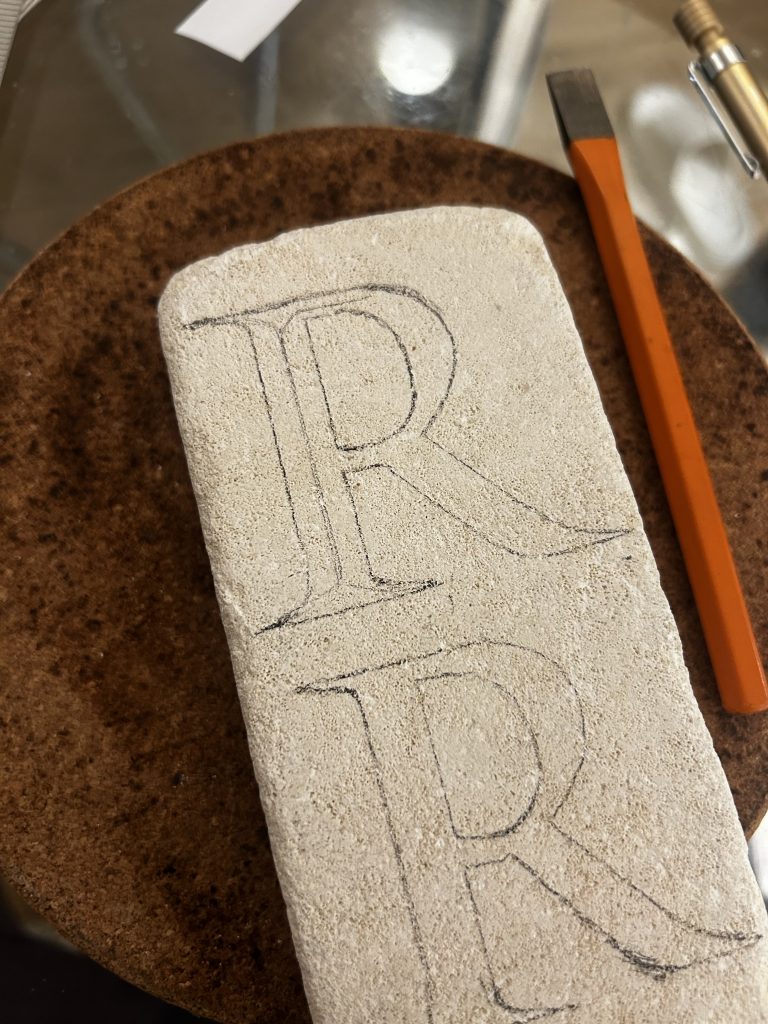

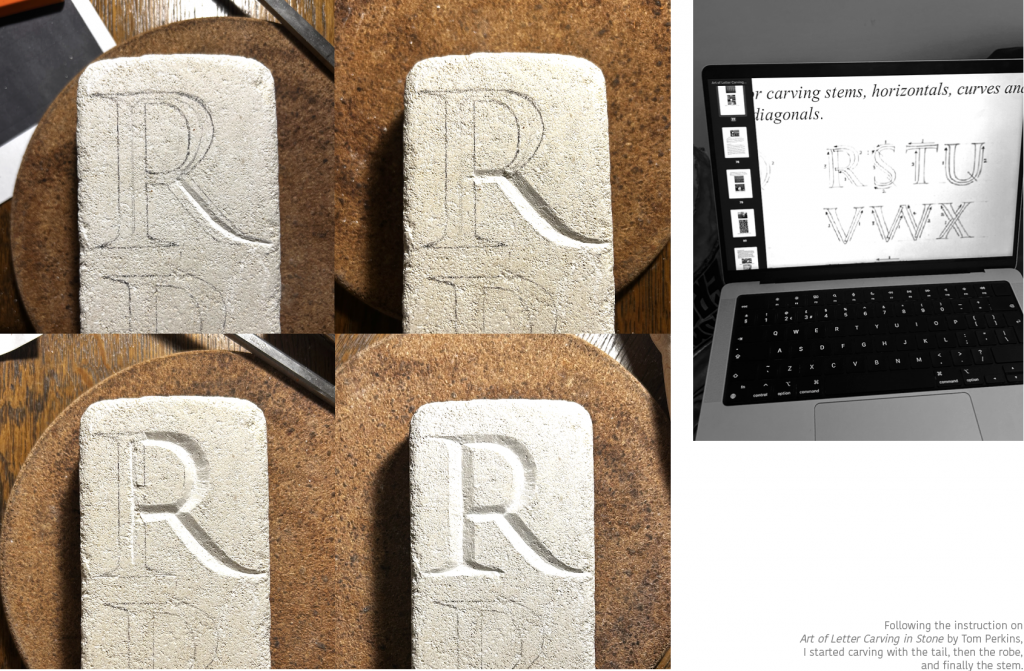

To replicate the intricate strokes of Gothic script, I chose to begin practising the most fundamental carving techniques with Trajan.

I traced the letter “R” from Trajan’s Column onto the limestone block using transfer paper and a pencil, and drew the centre lines of the strokes.

This was necessary because the carving would proceed from the central axis outwards towards both sides of each stroke.

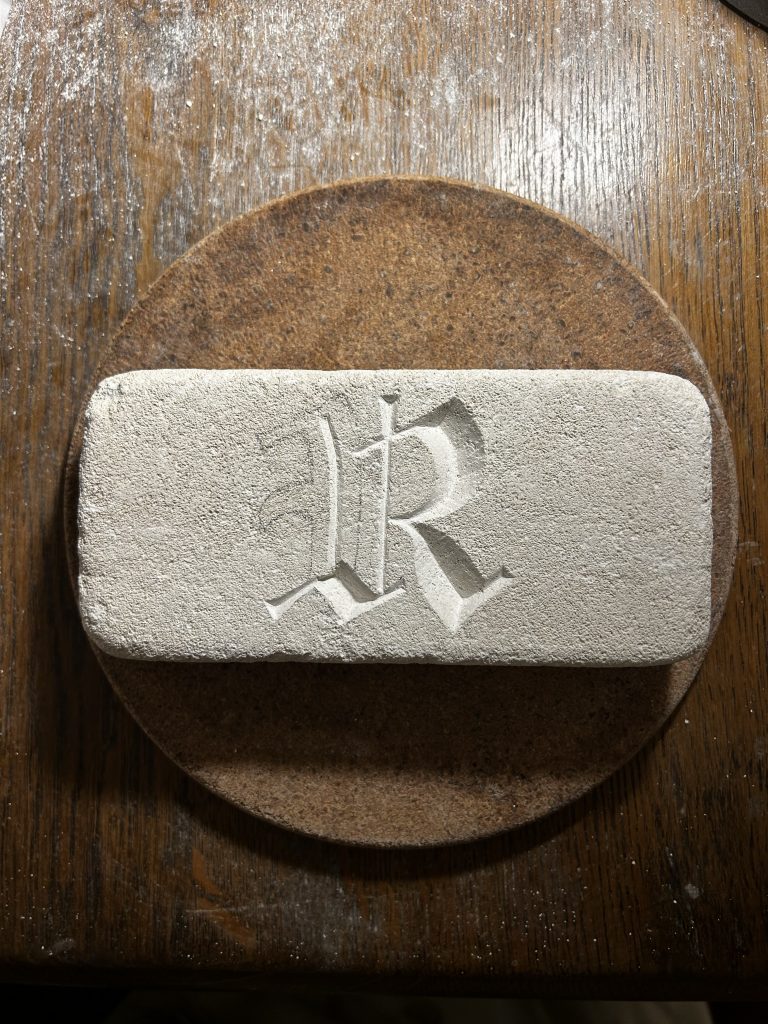

The Gothic R

I was unable to find the exact Gothic typeface that carved on St Virgin’s Church, so I reproduced it to transfer it on the brick.

By moving from the ‘native’ Trajan to the calligraphic Gothic R, it uncovered the rigid constraints of the medium. I found that while Roman capitals flowed naturally from my chisel, the Gothic forms forced me into a tedious process of sculpting negative space. This experience redefined typography for me as the fossilized memory of the tool that created it, whether that tool is a chisel, a quill, or any software.

Second Week’s Tutorial

Sharing my stone carving results with the group and Zarna elicited some unexpected reactions. They were surprised that instructional manuals for stone letter carving even exist. Interestingly, we discussed how these pedagogical resources seem exclusively dedicated to Roman Serif capitals. When asked if a Gothic guide existed, I confirmed it didn’t. In its absence, I appropriated the Trajan stroke order, specifically the bottom-up sequence (Tail → Lobe → Stem). This logic proved effective; it naturally accommodated the wrist’s torque, allowing for smoother execution of the curves.

While the feedback regarding content and linguistic bias was valid, Zarna’s advice to ‘keep constants’ resonated most deeply. It connects directly to our understanding of Conditional Design: randomness is not about abandoning control or allowing arbitrary outcomes, but rather defining the specific scope in which variation occurs. This insight compels me to approach next week’s iterations with a much more rigorous framework.

Leave a Reply